From populism to right-wing extremism - and why looking away is not an option

The shift of political discourse to the right is not a sudden event, but the result of a long development. Populism was rarely the final stage. It was the gateway. In many countries, it has now become the ramp through which openly right-wing extremist positions are brought into parliaments, governments, and the social mainstream.

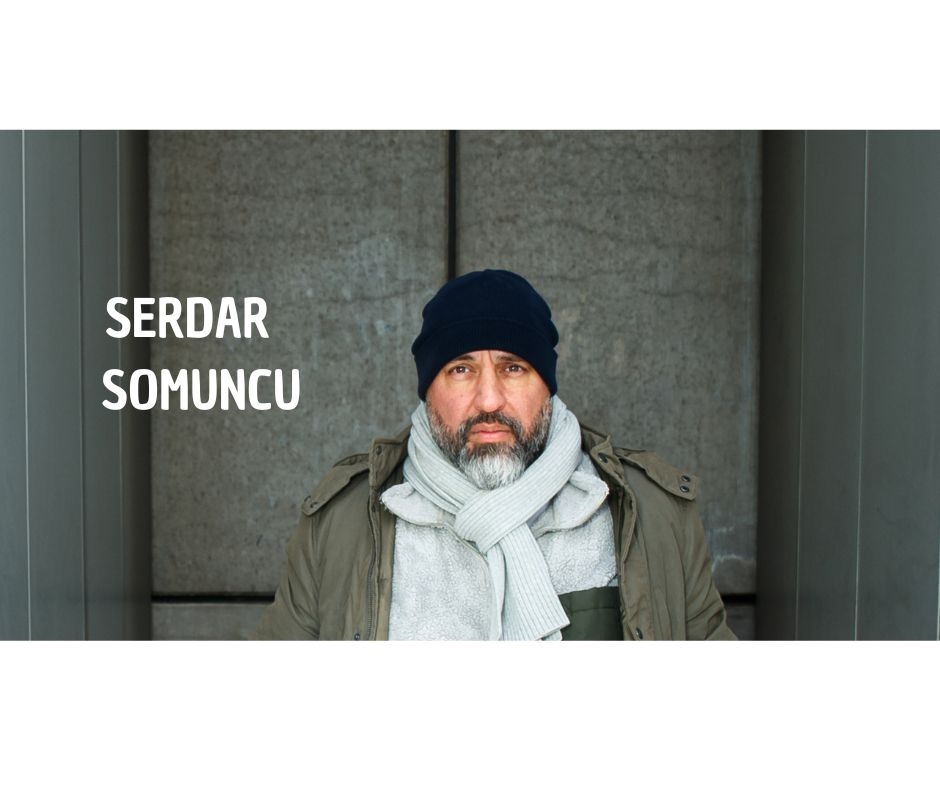

By Serdar Somuncu

By Serdar Somuncu

Historical Precursors: None of this is new

Anyone who thinks this is a phenomenon of the last five or ten years is mistaken. In Austria, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) already garnered around 27% of the vote in 1999 and entered government - a taboo-breaking act that at the time resulted in international sanctions. Today, it would hardly make headlines.

In France, Jean-Marie Le Pen laid the foundation with the National Front for what his daughter, Marine Le Pen, later perfected strategically. In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen surprisingly made it to the presidential runoff election (just under 17% in the first round). In 2022, Marine Le Pen achieved 41.5% in the second round - no longer a fringe phenomenon, but a real option for power. The renamed National Rally (Rassemblement National) is now more firmly established in many working-class and suburban communities than the traditional left.

Spain is no exception. With Vox, a clearly far-right party entered parliament for the first time since the Franco dictatorship. In 2019, it garnered 15% of the vote, and in 2023, it stabilized at around 12% - despite massive public criticism.

The new normal: Right-wing, but polished

What has changed is less the core of the ideology than its packaging. In Italy, Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia) governs under Giorgia Meloni. Historically rooted in the post-fascist milieu, the party won 26% of the vote in 2022 - with the promise of order, tradition, and national sovereignty, not with overt extremism.

In the Netherlands, the Party for Freedom (PVV) of Geert Wilders became the strongest party in 2023 with around 24%. The tone: less boisterous than before, the content: hardly changed. Islam as an enemy image, migration as a threat, national isolation as a panacea.

Hungary and Poland demonstrate the next stage. Fidesz won again in 2022 with over 54% of the vote. Law and Justice (PiS) garnered 43% in 2019. This is no longer just about electoral success, but about the systematic restructuring of the judiciary, media, and institutions--formally democratically legitimized, but in practice illiberal.

The currents: a right-wing mosaic

Right-wing extremism is no longer a monolithic bloc. There are at least four identifiable currents:

1. *The "bourgeois" national conservatism*

Clean suits, statesmanlike rhetoric, emphasis on family, order, and nation. Authoritarian in substance, moderate outwardly.

2. *The identitarian culture war*

Focus on "cultural identity," gender hostility, alleged threat from migration. Often resonates with conservative circles.

3. *Social Nationalism*

A welfare state, yes--but only for "our own." Successful among former left-wing voters, for example in northern France or eastern Germany.

4. *Open Radicalism*

Loud, provocative, deliberately transgressive. Smaller segments, but an important preparatory and mobilizing function.

These movements overlap, changing their guises depending on the audience and situation--and that's precisely what makes them so successful.

Numbers that can't be ignored

Between 2010 and 2024, right-wing extremist or clearly right-wing populist parties in Europe *doubled* on average--in some cases tripled--in terms of vote share and parliamentary representation. In several countries, they now either form the government or are the strongest opposition force. This is no longer a wave of protest. This is structure.

So what now?

Banning procedures may be legally necessary, but politically they are an illusion. They combat symptoms, not causes. They don't prevent Recurrence - in case of doubt, they accelerate the narrative of victims and martyrs.

What's missing is not pragmatism, but realism. The political center must relearn how to engage in conflict instead of merely managing it. It must implement mandates from voters instead of downplaying them. It must name problems instead of defusing them with language.

An open debate doesn't mean adopting right-wing positions. It means engaging with them on the ground. Those who refuse to do so cede the field to those who promise simple answers - and who reduce complex societies to simplistic enemy images.

The crucial question is not whether populism is morphing into right-wing extremism. It already is. The question is whether the democratic center is ready to assume responsibility again - in terms of content, language, and politics.

December 31, 2025

©Serdar Somuncu

"The new book - Lies - A Cultural History of a Human Weakness"

*Serdar Somuncu is an actor and directord director

LINK TO THE NEW BOOK

Anyone who thinks this is a phenomenon of the last five or ten years is mistaken. In Austria, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) already garnered around 27% of the vote in 1999 and entered government - a taboo-breaking act that at the time resulted in international sanctions. Today, it would hardly make headlines.

In France, Jean-Marie Le Pen laid the foundation with the National Front for what his daughter, Marine Le Pen, later perfected strategically. In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen surprisingly made it to the presidential runoff election (just under 17% in the first round). In 2022, Marine Le Pen achieved 41.5% in the second round - no longer a fringe phenomenon, but a real option for power. The renamed National Rally (Rassemblement National) is now more firmly established in many working-class and suburban communities than the traditional left.

Spain is no exception. With Vox, a clearly far-right party entered parliament for the first time since the Franco dictatorship. In 2019, it garnered 15% of the vote, and in 2023, it stabilized at around 12% - despite massive public criticism.

The new normal: Right-wing, but polished

What has changed is less the core of the ideology than its packaging. In Italy, Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d'Italia) governs under Giorgia Meloni. Historically rooted in the post-fascist milieu, the party won 26% of the vote in 2022 - with the promise of order, tradition, and national sovereignty, not with overt extremism.

In the Netherlands, the Party for Freedom (PVV) of Geert Wilders became the strongest party in 2023 with around 24%. The tone: less boisterous than before, the content: hardly changed. Islam as an enemy image, migration as a threat, national isolation as a panacea.

Hungary and Poland demonstrate the next stage. Fidesz won again in 2022 with over 54% of the vote. Law and Justice (PiS) garnered 43% in 2019. This is no longer just about electoral success, but about the systematic restructuring of the judiciary, media, and institutions--formally democratically legitimized, but in practice illiberal.

The currents: a right-wing mosaic

Right-wing extremism is no longer a monolithic bloc. There are at least four identifiable currents:

1. *The "bourgeois" national conservatism*

Clean suits, statesmanlike rhetoric, emphasis on family, order, and nation. Authoritarian in substance, moderate outwardly.

2. *The identitarian culture war*

Focus on "cultural identity," gender hostility, alleged threat from migration. Often resonates with conservative circles.

3. *Social Nationalism*

A welfare state, yes--but only for "our own." Successful among former left-wing voters, for example in northern France or eastern Germany.

4. *Open Radicalism*

Loud, provocative, deliberately transgressive. Smaller segments, but an important preparatory and mobilizing function.

These movements overlap, changing their guises depending on the audience and situation--and that's precisely what makes them so successful.

Numbers that can't be ignored

Between 2010 and 2024, right-wing extremist or clearly right-wing populist parties in Europe *doubled* on average--in some cases tripled--in terms of vote share and parliamentary representation. In several countries, they now either form the government or are the strongest opposition force. This is no longer a wave of protest. This is structure.

So what now?

Banning procedures may be legally necessary, but politically they are an illusion. They combat symptoms, not causes. They don't prevent Recurrence - in case of doubt, they accelerate the narrative of victims and martyrs.

What's missing is not pragmatism, but realism. The political center must relearn how to engage in conflict instead of merely managing it. It must implement mandates from voters instead of downplaying them. It must name problems instead of defusing them with language.

An open debate doesn't mean adopting right-wing positions. It means engaging with them on the ground. Those who refuse to do so cede the field to those who promise simple answers - and who reduce complex societies to simplistic enemy images.

The crucial question is not whether populism is morphing into right-wing extremism. It already is. The question is whether the democratic center is ready to assume responsibility again - in terms of content, language, and politics.

December 31, 2025

©Serdar Somuncu

"The new book - Lies - A Cultural History of a Human Weakness"

*Serdar Somuncu is an actor and directord director

LINK TO THE NEW BOOK

Write a comment